It’s a question we often get asked as advisers, especially when markets are turbulent. ‘My investment has gone down, should I just withdraw it now and put my money in the bank?’ Although you may rationally know that investing can sometimes involve your balance going both up and down, it’s not always that easy to sit back and ride it out.

Over 2023 I’ve been doing a course called “Behavioural Finance – Investment Decision-Making”. My reason for studying this is to better understand the emotions and biases that drive investors’ decisions. My thinking was, if I know more about this, I’ll be a more effective adviser. I’ll understand my clients better and be able to help them through the inevitable ups and downs of their investment journey.

It’s a huge area of study which I plan to continue with, but even at this early stage some main points really resonate with me, and reflect what I’ve observed through my years being an adviser.

Changing perspectives on investor behaviour

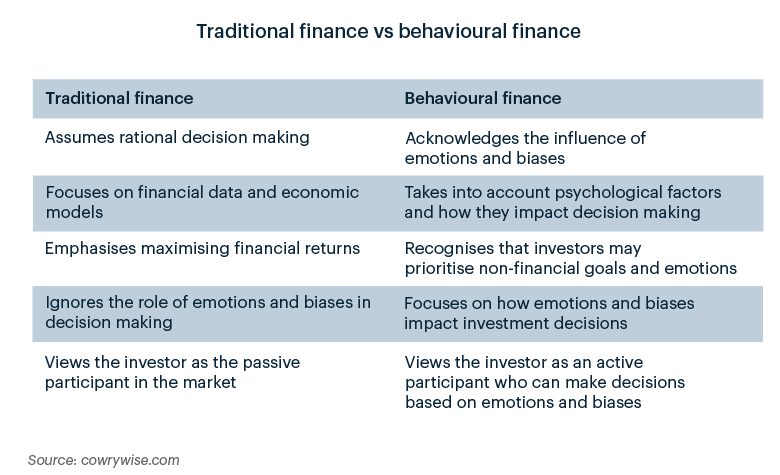

Academic research and thinking on investor behaviour has changed over time. It was during the 1960’s and 70’s that a strong school of thought that I’ll refer to as “traditional finance” took hold. This formed the basis of many of the lessons I was taught during my university years. The basic assumptions are that humans are rational and will make decisions based on all the available facts to maximise their financial returns.

More recently, psychology and the study of what drives decisions, including emotions and biases – has been re-established, circling back to a more holistic way of understanding, and also trying to predict, investor behaviour.

We all use mental shortcuts

We live in a very fast paced world where there is so much to take in – sights, sounds, smells, sensations, ideas. To cope with this we use rules of thumb and past experience to make sense of it all without overloading our brains. There is no way we can obtain, process and understand all available facts at any one time. These mental shortcuts we use to function in the world are known as heuristics.

An example of this in the investment world is that people will look at past investment returns and make a decision to invest, based on the expectation that these will continue. This is a mental leap they make about future investment returns which encourages them to take action.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have been described as the “Lennon and McCartney of social science”. Their area of research and publications combined economics and psychology and resulted in Kahneman winning the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002. They looked at how people choose, especially when there is uncertainty.

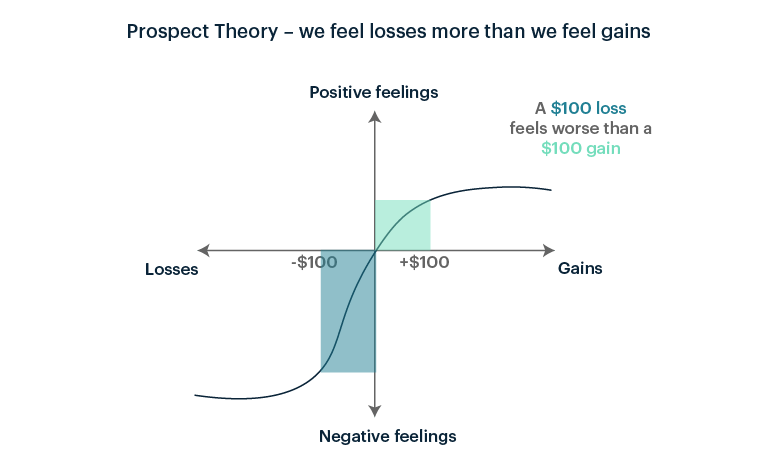

They developed a theory called “Prospect Theory” to help explain observed behaviour. Part of Prospect Theory is the idea that we feel losses more than we feel gains. You can see from the chart below that the pain we feel for losing $100 is much greater than the joy we feel for gaining $100.

Are we loss averse rather than risk averse?

Imagine I present an investment to you as having a forecast annual return of up to 20% for any given year. It sounds pretty good, and it’s likely to encourage you to invest.

Alternatively, I could present an investment to you as having a forecast annual return that could be as low as -20% in any given year.

Both investments are the same, yet presented with the second option, you’re unlikely to choose it. Rather than “risk averse” we are all “loss averse”. Your decision can be influenced simply through how the likely outcome is presented.

This is one of the reasons why the investment industry is regulated. To ensure fund managers don’t present future returns in a flattering light, the Financial Markets Authority requires all KiwiSaver providers to use the same rate of return per strategy in their retirement calculators.

What’s your reference point?

Recognising an individual’s “reference point” is another take out from Prospect Theory. When you are evaluating the success or otherwise of an investment strategy, what is your reference point?

Is it your initial investment amount? If your balance drops below an initial investment value, do you consider withdrawing once you get back to even?

Is it term deposit rates? Is this the minimum return you expect to earn, otherwise your investment is not a success?

Is it the return on your partner’s or neighbour’s investment? Do you discuss your investments with friends and family and feel bad if your annual return is not as good as theirs?

Is it a dollar value goal you’re aiming for? Do you have a number in mind of what you want to have invested before you stop work? How does it feel when that goal seems to get further away and you need to work longer than planned?

A reference point can be quite different for each person, and it will likely drive behaviour. As advisers we need to understand yours.

Understanding your timeframe

One of the most common themes in our client conversations revolve around time, like the age-old sayings of “it’s time in the market, not timing the market that works”; “Zoom out from the here and now look at the long term”; “Hold the line and stick with it to reap the rewards down the track".

I don’t think there’s any debate that all investments need time to deliver. My goal in studying is to get beyond the words and be more effective in helping clients really understand their investing timeframe when emotions and biases creep in and demand action.

Sometimes selling investments can be the right course of action, but many times it’s not. By asking questions and discussing choices, advisers can try to help investors make good decisions.

Talk to us

If you’re feeling unsure about whether your investment strategy is right for you, our team are always happy to help. We can talk you through your investment timeframe and discuss your investing options. You can chat to us online, drop us an email or call us on 0508 347 437.