One of life’s pleasures that I really missed during the COVID period was live sports. International rugby recently kicked back off for another year with the All Blacks concluding an enthralling series against Ireland (congratulations to any Ireland supporters).

Watching these games, I was reminded of a saying that our coaches often told us: “play what’s in front of you”. This is telling the players not to worry about the scoreboard, what has just happened, what might happen, or anything else other than what the players can control in that instant.

This advice is also apt for investing in these uncertain times. The risks of a recession have risen. Markets have fallen in response. The S&P 500 Index fell 23% from its peak, before ending June around 20% down. This is not far from the median market 24% decline in historic recessions.

But this is all backwards looking. Now more than ever we need to ‘play what’s in front of us.’

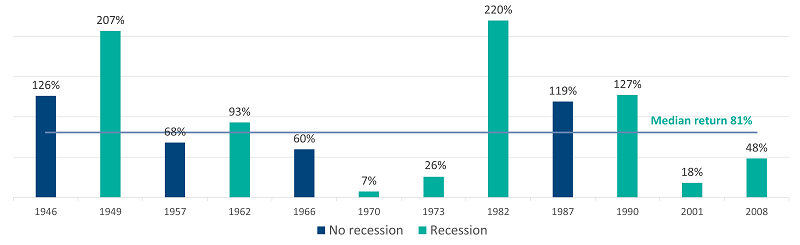

This does not mean trying to pick the short-term moves in the markets. Recessions are inherently difficult to predict in terms of timing, duration, and magnitude. While the median market decline in a recession may be 24%, the range of market moves during recessions is wide, from a 14% decline in 1960 to a 57% decline in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)

Could things get worse? If we go into a recession, markets will probably go a bit lower. But do we think this is going to be another GFC or dot-com level crash? Probably not. 2008 was a unique circumstance with a near collapse of the global banking system and a major US housing crash. And market valuations in 2021, while elevated, were well below the stratospheric levels we saw in the dot-com crash.

People are understandably focussing on the short-term and potential for further downside – but trying to time and profit from short-term market moves is very difficult. Even if you predict a further downturn, are you going to be able to correctly call the bottom and have the fortitude to get back in when everyone else seems to be doing the opposite. History has shown that for most investors – this is not the case.

And if you are wrong, you are potentially giving up strong gains.

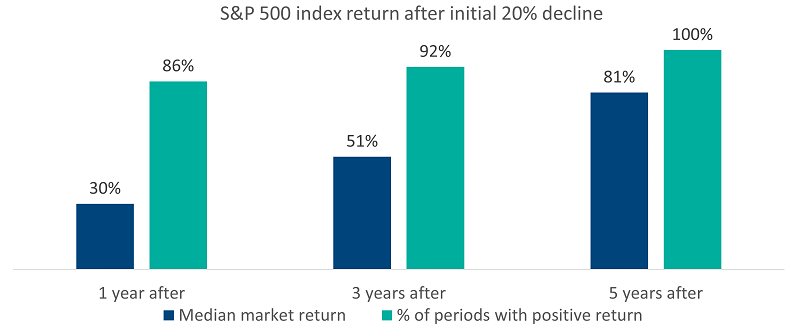

We analysed the historic returns following the market dipping into a bear market (defined as a 20% decline). This has occurred fourteen times post-World War 2 (excluding the current decline). Once the markets dropped into ‘bear territory’, 12 out of those 14 occasions saw positive market returns in the following twelve-months, with a median return of around 30%. The median time to get back to the prior market peak was sixteen months from the point the market dips into a bear market.

As we look further out, both the probability of a positive return and the expected return increase. On a five-year horizon, the market returns were all positive with a median return of 81%.

Even in the worst period for investors during the 1970’s, the return was still 7%. The three worst markets returned 17% on average. That is not terrible for a ‘worst-case’ scenario. In the other nine bear markets for which we have data, the subsequent five-year returns averaged nearly 120%.

Recessions and bear markets are an inevitable part of investing. But like in sports, when a team (or investor in this case) falls behind on the scoreboard, often they start making mistakes. Investors focus too much on the scoreboard, stung by recent losses. Or they focus on how much worse things could get. They start to forget any plans they had in place.

Instead, investors should be playing what is in front of them, ignoring the noise and focusing on the longer-term. Yes, things could get worse, but history shows us that even on the few occasions this has occurred, investors would have still seen positive returns over the next five years. In most cases, events were not as bad as expected and investors that stayed the course were rewarded with a period of strong returns.