Much like us here in New Zealand, our cousins across the ditch have struggled with the cost-of-living crisis over the last few years. And while inflation seems to have peaked and is trending down, Australian (and New Zealand) households remain under pressure as the cumulative price increases over the last three years have reduced real income and eaten into savings.

In Australia, annual real per capita household disposable income declined for a 10th successive quarter to December 2024 and is now down ~8.1% since the peak in June 2022. The pressure is being felt most in the 18-29 and 30-39 age cohorts who are spending less on essential goods, with only those aged 60+ spending more than inflation.

So, who is to blame?

People are understandably frustrated and looking for someone to blame. Unsurprisingly, no one has put up their hand and issued a public mea culpa for the excessive stimulus that was ultimately at fault for the inflation spike, and the root cause of the cost-of-living crisis we are still dealing with today. With pressure building on households and no obvious solution in sight, people have looked to attribute blame to where they feel it the most acutely - the weekly grocery shop. Everyone needs to buy groceries, and the frequency and repetitive nature of the weekly shop means it is the easiest place to observe the increase in pricing.

Australian households spend around 10% of their net income on groceries, and for lower income households this can be as high as ~25% of their net income. So, it goes without saying that households felt every bit of the ~24% increase in grocery prices over the last five years.

It’s then no surprise the public ire in Australia has been directed at Woolworths and Coles. Together they account for ~67% of Australian supermarket retail sales and combined they earned A$2b+ of profits in 2024 - a big number when viewed in isolation, and a red rag to a bull in the current cost-of-living crisis.

In addition, with Australians heading to the polls this year and cost-of-living taking centre stage, it's easy to see why the government has been so dogged in its pursuit of the supermarkets and its price gouging accusations.

Plethora of inquiries

In January 2024, the Australian Government announced an ACCC inquiry into Australia’s supermarket sector. The inquiry explored, amongst other things, the pricing practices of the supermarkets and if they misled consumers through discount pricing claims.

This wasn’t the only inquiry, with at least eight separate federal, state and regulatory inquiries underway at one point in 2024. This included the Senate inquiry into supermarket concentration and pricing, and a Grocery Code review.

The big question – are supermarkets taking the mickey out of Australian consumers?

After an intensive investigation, including the supermarkets providing “thousands of documents and millions of data points” and public hearings involving senior executives of Woolworths, Coles, Aldi, Metcash (representing the independent supermarkets) and other stakeholders, the ACCC released its final report on the 21st March. While it provided a range of recommendations for legislative and policy reforms among other actions, it was unable to identify excessive profit margins, or price gouging by the supermarkets.

Grocery prices had indeed increased significantly in the last five financial years, but the inquiry rightly found this was in most part attributable to increases in the cost of doing business across the economy, including the production costs for suppliers which have gone up significantly as well.

Woolworths, the largest Australian supermarket by market share, has seen its operating margins remain flat between the first half of 2020 and the first half of 2025 (after adjusting for the impacts of industrial action in the first half of 2025). However, on a statutory basis, margins have decreased by 40 basis points over this period. This is despite higher revenues driven by inflation, which counters the 'overearning' claims. While Woolworths' margins are higher than in some other countries, they are actually 40% lower than in 2014. This is significant because the ACCC targeted Woolworths and the sector due to concerns over high and expanding margins.

How do Australia and New Zealand compare to global peers?

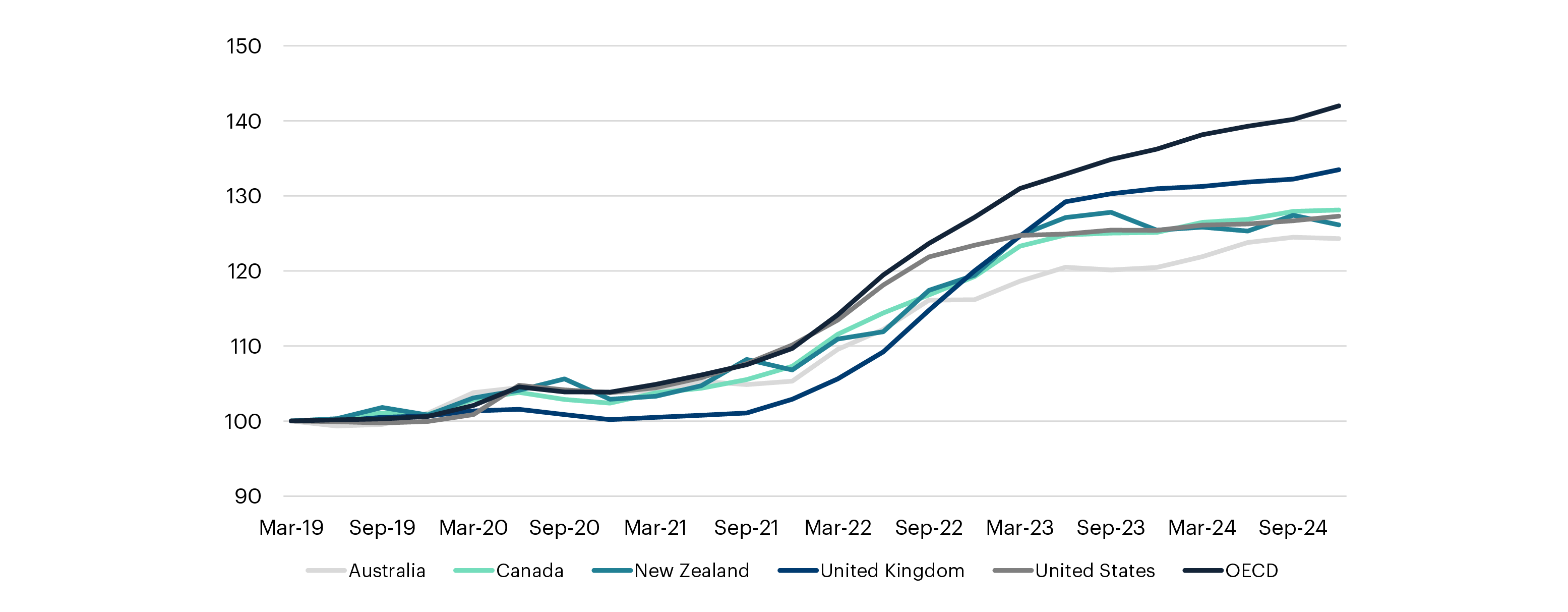

At a high level, grocery prices have increased ~24% over the last five years in Australia, slightly above general inflation which is ~22%. While it is of little consolation to an under-pressure consumer, Australian grocery price inflation has been below the majority of the OECD constituents and the OECD average.

So, if the supermarkets aren’t the cause – what is?

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical, and weather events, suppliers have faced rising costs. To manage these, they've asked Woolworths (and other supermarkets) to pass on these costs through increases in shelf prices. The ACCC highlighted significant cost hikes in fuel, energy, labour, and more that impacted the suppliers. Between November 2021 and January 2023, Woolworths received 4.5 times more cost increase requests from suppliers. Over five years, food manufacturing costs rose by 29%, outpacing the 24% increase in grocery prices.

Despite investigations, the ACCC found no evidence of price-gouging. The ACCC’s final report made 20 recommendations, focused on measures for better price transparency and reducing supermarket power over suppliers.

Less than 10 days after the ACCC final report failed to find evidence of price gouging, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was calling for a taskforce to be set up that will look at…wait for it – price gouging by the supermarkets. It would come as no surprise that on the previous day he had called for the federal election to take place on 3 May.

How does New Zealand compare?

Not to be outdone, on the same day as Anthony Albanese was calling for another review of price gouging in Australia, New Zealand Finance Minister Nicola Willis announced that the government had hired an external adviser to provide advice on ways to restructure the supermarket duopoly in New Zealand.

The restructure could take the form of a third player in the market to compete with Woolworths NZ and Foodstuffs (owner of franchises Pak’nSave, New World and Four Square), or it could be in the form of breaking up the two incumbents.

Much like in Australia, it is always easy to blame supermarkets for price gouging. However, a quick look at the financials of Woolworths NZ (owned by Woolworths Australia), and its clear it is earning a decent return, but not excessive. Woolworths NZ recognised NZ$100m of operating profits in 2024 at a margin of 1.3% (before interest and tax). This is well below the margins of its international peers Walmart 4.3%, Kroger 3.1%, Tesco 4.3%, Sainsbury 3.2% and Carrefour 2.5%.

As with Australian supermarket profits, while the dollar value of the profits may seem large, the margins do not match the rhetoric of price gouging.

What’s the future of supermarket competition in New Zealand?

Arguably in New Zealand, like Australia, the planks for a competitive industry are largely already in place. In New Zealand, Costco opened its first mega store in Westgate, Auckland and is actively seeking to add further stores in strategic locations. The likes of Kmart, Chemist Warehouse, Bunnings and The Warehouse are encroaching on the supermarket’s range and taking share in nonperishables. If we roll forward five to ten years, then it is more likely than not that these stores will have taken further share from Woolworths and Foodstuffs.

However, it is tougher to see another large international player (in addition to Costco) entering the New Zealand market. Factors like population density, a relatively small population (and therefore less volumes) and the logistical challenges of getting goods here (and to two separate islands) mean it is just not attractive enough.

But let’s see what (another) review brings in.

Talk to us

If you have any questions about your investment or would like to make sure you have the right investment strategy to reach your financial goals, get in touch with us – our team are always happy to help.

This article was originally published in the NBR on 8 April 2025 (paywalled).