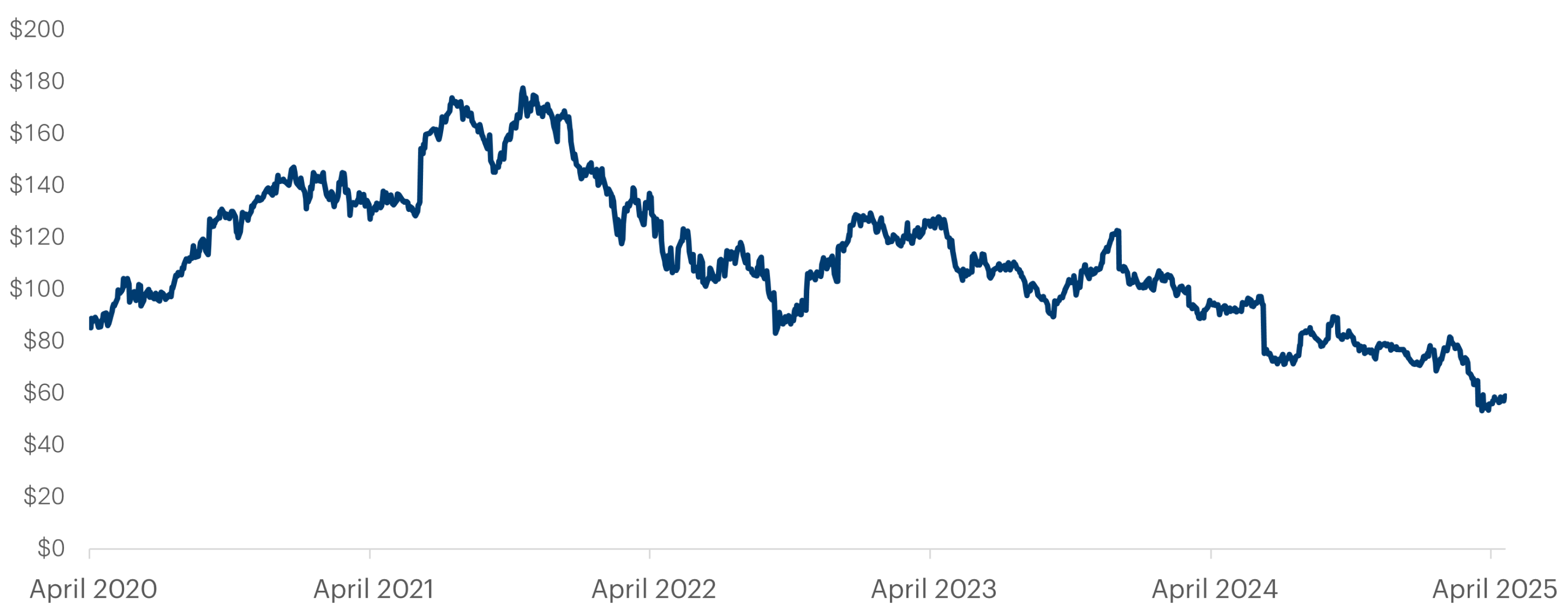

Recently retired Warren Buffet famously said, “be fearful when others are greedy and to be greedy only when others are fearful”. Shares in Nike, the world’s largest footwear and apparel manufacturer, have fallen 68% since the November 2021 peak. The share price would imply investors are fearful, but is it time to be greedy?

What happened?

Put simply, Nike appointed a new CEO, John Donahue, who shifted the company away from its core.

Historically, Nike has been a brand focussed on innovation and performance. It combined this with creativity and storytelling to leverage the emotional power of sport and in doing so created deep, personal connections with the consumer. Nike had strong relationships with retailers, where they – especially in the United States – occupied most of the shelf space.

When Mr Donahue, who had a Silicon Valley background, started in January 2020 he moved Nike towards being a digitally focused, direct-to-consumer company. And he shifted it from being category focused (e.g. running, football, basketball) to being gender focused which mimicked general brands like Gap and H&M. This decision was reversed three years later, but not before Nike lost thousands of years of product experience and expertise through layoffs.

This digital shift seemed to go well at the beginning, largely due to COVID and the challenges traditional retailers faced with lockdowns. Nike’s direct-to-consumer business was flying, justifying the CEO’s important strategic shift into e-commerce.

However, the post-lockdown reality slowly and regularly showed there were holes forming in the new CEO’s strategy.

So, what was the result?

With the benefit of hindsight, the outcome was pretty obvious. Consumers, who are largely occasional buyers, did not follow Nike online, but returned to their pre-COVID retail habits. In store, Nike sneakers didn’t have the shelf space they once did, so consumers opted for other brands. The open space Nike left behind was gladly filled by brands such as New Balance, ASICS, Brooks, but more importantly new innovative brands such as Hoka and On Running.

These new brands started winning market share, using a similar playbook that Nike founder, Phil Knight, used in the early days to attack incumbents – focusing on specialised categories such as running and driving innovation.

In theory, pushing more product through DTC channels should be more lucrative as the brand captures the retail mark up. Instead of selling a pair of Jordans to a retailer for $100, which they on sell at $160, Nike can sell the same sneakers direct to the consumer at full price. This results in higher gross margins (c.60% versus 45%), but similar operating profit margins, as the DTC model has additional costs like warehousing and shipping. However, Nike’s operating profit dollars in this transaction are around a third higher (12% of $160 versus 12% of $100) and this drives earnings growth.

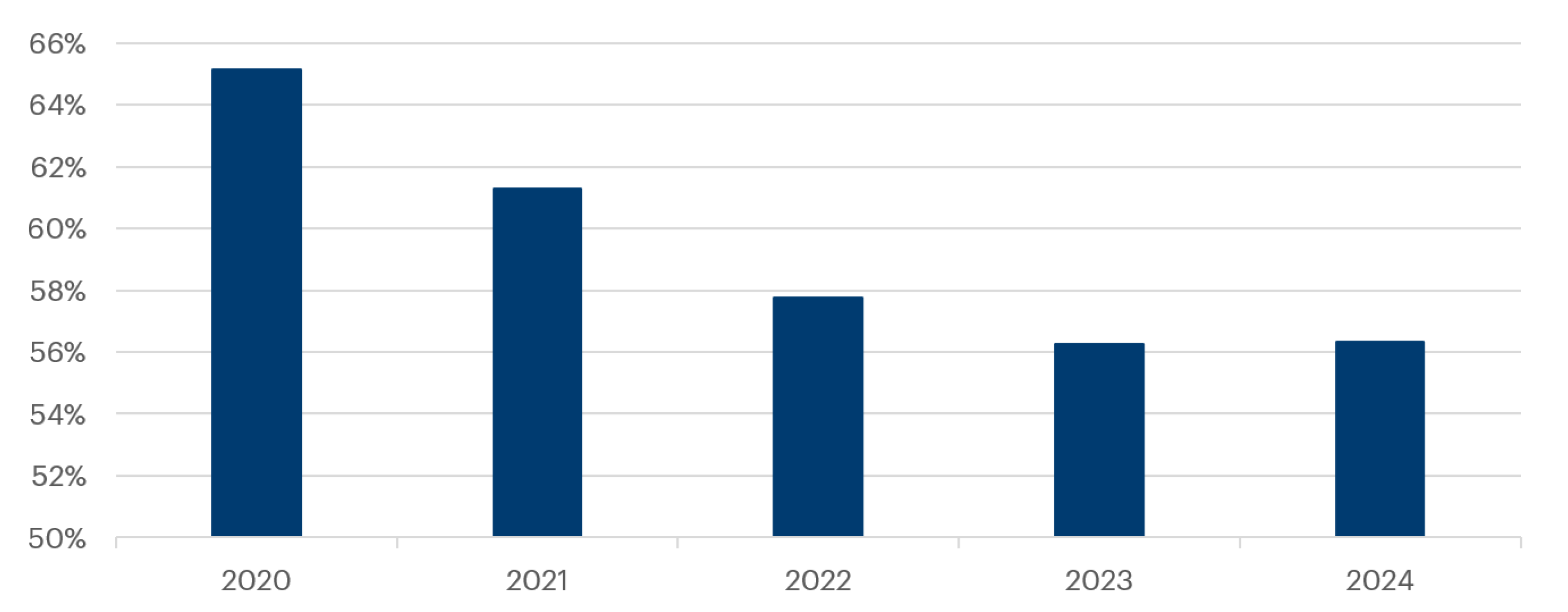

The theory played out well for a while. DTC revenue grew at 32%, 14% and 14% in financial years 2021, 2022 and 2023 respectively. Concurrently gross margin increased from 43.4% to peak at 46% in the 2022 financial year.

But underneath this, trouble was brewing. Before COVID, Nike turned over inventory around four times a year. But with the DTC strategy, inventory levels started to rise, and turnover fell to around three times a year by the first quarter of the 2024 financial year. Nike lacked the data and systems to predict demand and therefore lack the knowledge and discipline to make this strategic operational shift.

Combined with an innovation deficit due to the loss of category expertise, Nike found themselves increasingly reliant on a few franchises (Jordans, Air Force Ones and Dunks), that were approaching the end of their lifecycle, to drive sales.

The growing focus on e-commerce from DTC channels and the lack of product innovation resulted in discounting, which hurt profitability and damaged the Nike brand.

Admission of error

In October 2024, Elliott Hill – who started at Nike in 1988 as an intern and retired in 2020 – was named CEO. Hill was quick to declare “Nike’s back” in interviews and his initiatives have been clear:

Restore a balanced marketplace between the Nike digital (DTC) and wholesale channels (retailers). Hill has prioritised reconnecting with key retail accounts and wants to win back shelf space from other brands.

Refocusing on product innovation to reduce reliance on flagship sportswear franchises. This is a return to putting sport at the centre of Nike’s core with a focus on running, basketball, training, football and sportwear. Since Hill started, there has been around a 10% increase in product-related job postings at Nike.

Why should Nike win again?

Their competitive advantage, or moat, remains intact.

In the 2025 financial year, which finishes at the end of this month, Nike is expected to spend US$4.6billion (around 10% of sales) on marketing and sponsorship. Competitors – other than Adidas – don’t come close to that. When you combine the two sportwear giants’ fire power, it’s no surprise that smaller competitors are crowded out of most major sports team and player sponsorships.

If Nike retains the quality of the brand, they will most likely sign the highest percentage of each generation’s best athletes because they can afford to pay them, and the athletes want to be in the Nike stable. The pool of the best never gets bigger. There are always only the same number of top 10 tennis players, top 10 football players, NBA and NFL superstars that really move the needle.

The latest example is US college basketball sensation and the biggest name in women’s basketball, Caitlin Clark. Adidas, Puma and Under Armour all wanted to sign Clark, but Nike won with an eight-year US$28million deal along with a signature shoe. Nike priced competitors out of the race.

In the case of LeBron James, Nike offered US$90million versus Reebok’s US$115million and still won. As James Benedict wrote in Esquire, the incredible story of how Nike signed LeBron James: “There were buildings [at Nike’s headquarters] that featured larger-than-life images of the immortals, Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, Bo Jackson. LeBron entered the Mia Hamm building and walked down a long hallway lined on both sides with glass cases containing Air Jordans and other iconic sneakers worn by NBA stars. At the end of the hall was one empty case that was illuminated by a light, making it easy for LeBron to envision his shoes in the hallowed passageway.” Who could resist?

Yes, in the short term, some trends or technology might have an edge. Like finding the “best” foam for running shoes to cater to current consumer taste. But while innovation and distribution are important, what differentiates Nike from competitors is their ability to sponsor the greatest teams and athletes, and to tell the best story to inspire the everyday person.

Is it time to be greedy?

Nike seems to be another example of an investment in which investors focus too much on fixable strategic missteps and competitors’ temporary strengths, while undervaluing their long-term competitive advantage and the potential positive outcomes. As Warren Buffett said, “the products or services that have wide, sustainable moats around them are the ones that deliver rewards to investors.”

This article was originally published in the NBR on 13 May 2025 (paywalled).

The managed investment schemes managed by Fisher Funds hold shares of the following companies mentioned in this column: Nike, Adidas.

Talk to us

If you have any questions about whether you have the right investment strategy for your retirement goals, you can get in touch with our friendly team – we’re here to help.