The recent shortages and resulting price increase of eggs has shown us the impact that changes to environmental regulations can have in the short term. Likewise, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) policies in investments can have both short and longer-term implications on investment returns, so need careful consideration.

I was initially surprised at the persistence of the egg shortage at our local supermarket. The recent addition of a sign pointing to regulation shed some light on the situation. In 2012, legislation was introduced in New Zealand banning battery-caged hens, with the ban coming into force in January 2023.

As the January 2023 deadline loomed, this led to supply leaving the industry. Some producers have preferred not to invest in the required infrastructure required to meet the new regulations. Presumably the added production complexities (and cost) of free-range production has also been a factor in these decisions.

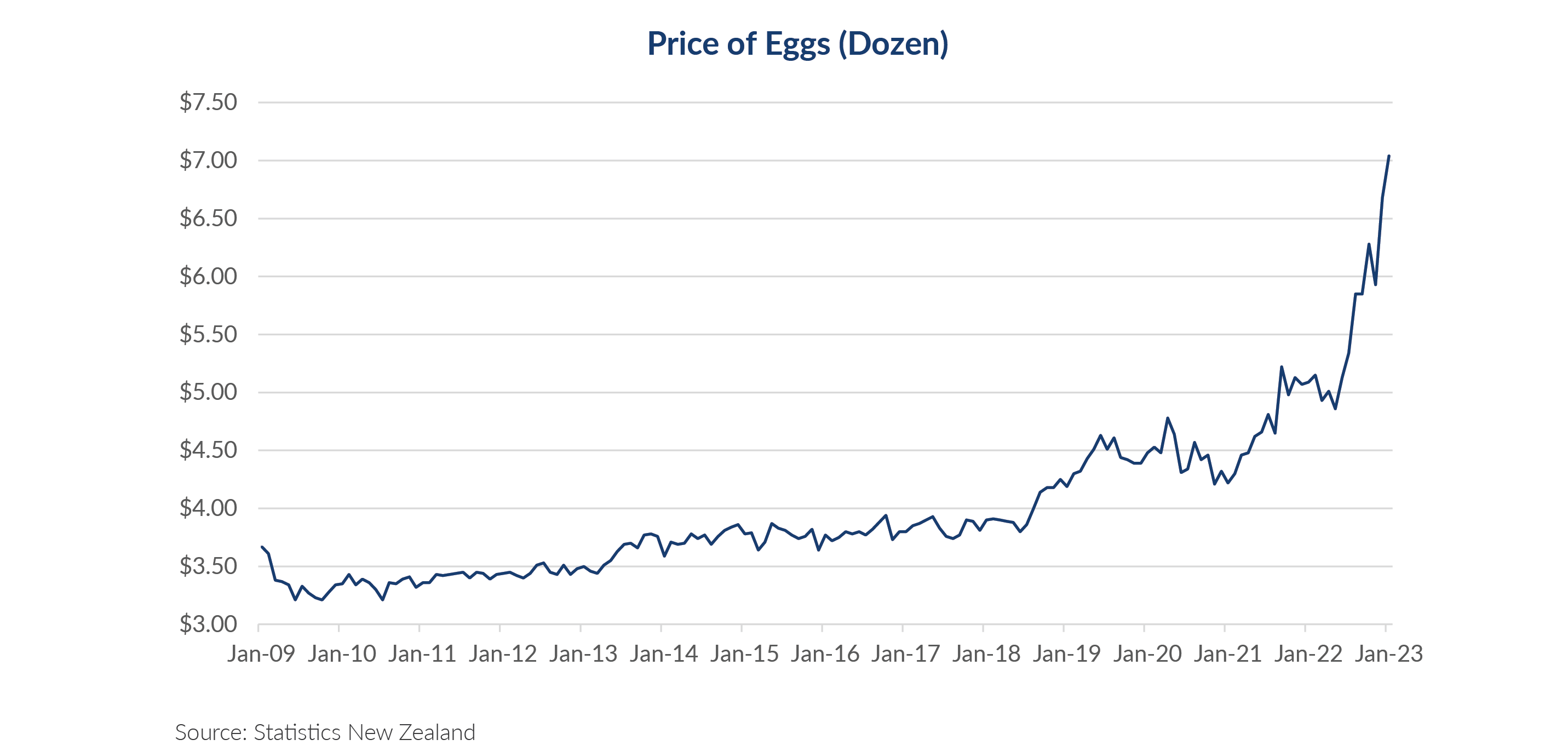

Economic textbooks tell us that if supply of a product falls, this generally leads to higher prices. And this is indeed what we’ve seen as egg prices have increased 85% since June 2018.

In theory, higher prices will also encourage new supply to be added (given the more attractive economics of producing eggs) and pricing equilibrium may once again be restored. It will be interesting to see how long this takes to play out in this instance.

Trade-off between financial and environmental costs

The environment is the E in the ESG acronym, – important considerations for fund managers these days when evaluating investments. From an environmental standpoint, the change in egg production regulation is clearly beneficial and society has rightfully required the standards of animal welfare to be lifted through time.

However, higher environmental standards often come with visible, material short-term cost increases for consumers, as we’ve seen with the eggs example. It’s unfortunate the timing of this legislation coincided with a sharp increase in the cost-of-living. The architects of the legislation could not have foreseen that back in 2012.

This highlights the importance of thinking longer term when framing up regulation, from both a financial and environmental perspective. Economic and environmental conditions change. Policy needs to be robust enough to be sustainable in both respects.

That’s not to say the egg regulation is poorly thought through. I suspect many people would prefer to pay more for eggs knowing hens live in better conditions, and the increased cost of eggs is unlikely to have negative ramifications in a broader economic context. But, equally, it is not free of cost. These higher prices will have a bigger impact on some parts of society than others.

This is also only one slice of environmental regulation. How much would consumers actually be prepared to pay, in aggregate, for environmental standards to be lifted across the economic landscape before we see a societal or political backlash?

The increase in the oil price (and cost of petrol at the pump) over the past few years, for example, is partially a consequence of underinvestment in fossil fuel reserves. This has been driven by environment-related policy and regulation. Exacerbated by the energy crisis in Europe and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there has been a sharp about-turn already by a number of governments on energy policy.

Sustainability: everyone has a role to play

Sustainability is multi-faceted.

It applies to the environment – ensuring that when we look back at our time on earth, we can be proud of our conduct and the state we left the planet in for future generations.

It applies to policy – regulators and governments must balance the competing forces of higher financial costs of policies and their immediate impact on people already under financial pressure against the long-term environmental cost of not making changes.

It applies to companies – as environmental standards and regulation evolve, companies need to adapt and position themselves for the future. Free-range egg farmers are still in business, battery-caged egg farmers aren’t.

And it applies to investors. Companies with unsustainable business models will make for poor long-term investments. In the short term, imbalances in the multi-decade-long journey to a decarbonised future can make for attractive shorter-term investment opportunities. Companies mining thermal coal, for example, have done well for shareholders in the past few years.

Weighing up the ethics of ESG policies against the shorter and longer-term impacts on financial returns is not easy. Hard decisions need to be made.

But, as the saying goes: you have to break a few eggs to make an omelette.

This article was originally published in the NBR on 21 February 2023.