Negative press headlines can play on investors’ deeply ingrained biases and natural risk aversion. But keeping short-term news in a longer-term context can help investors stay the course, and ultimately benefit from the wealth creation typically delivered by growth assets like shares and property.

Financial journalists are great at writing emotive and attention-grabbing headlines. On the 19th of July, my daily scroll through the Washington Post uncovered an alarming headline: “Delta variant fears send Dow tumbling more than 700 points in worst one-day decline of 2021”. Late in the month we were also faced with major declines in Chinese stocks as the Chinese Communist Party cracked down on a handful of US-listed Chinese companies that weren’t towing the party line. This again resulted in dramatic and ominous newspaper headlines.

A decade of crises

It hasn’t just been a month of headlines. The last decade or so seems to have seen more than its fair share of crises. COVID created a huge market event – with the New Zealand and US markets both plunging over 30% in record times. Before that we had the global financial crisis, and in between we have had a plethora of events including the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, rising populism (with Trump & Brexit), and the US-China trade war. Each of these events got a lot of airtime and caused market jitters.

Headlines about the latest crisis often attract reader intention. They create fear and play on human psychology. But if we make decisions based on these headlines, we can do a lot of damage to our finances.

Loss aversion and human behaviour

While economic textbooks say humans are rational and unbiased decision makers, humans don’t always make rational decisions. We are subject to a range of deeply ingrained biases that come to the fore in times of stress - when our reptilian brain and fight-or-flight instincts kick in.

One such bias, which was identified by psychologist Daniel Kahneman is called loss aversion. Kahneman’s work has become more broadly discussed since he published a best-selling book on the topic, Thinking, Fast and Slow.

The crux behind loss aversion is that people feel more pain from loss than they feel pleasure from an equal gain. Economic theory had previously assumed that a rational person would weigh gains and losses equally. But according to research, with a $100 loss, you lose twice as much satisfaction as you gain if you win $100.

One investment implication of loss aversion is that it can lead investors to hold more money in cash or bonds than is optimal, instead of investing in growth assets like shares and property.

Loss aversion, combined with these dramatic headlines, can cause us to make irrational decisions. This makes it even more important to keep short-term noise in context.

A longer-term lens can calm nerves and smooth out volatility

While the share market can be volatile in the short term, long-term outcomes for disciplined investors tend to be good. Over the long-term businesses tend to generate cash flow and grow, and this rewards shareholders.

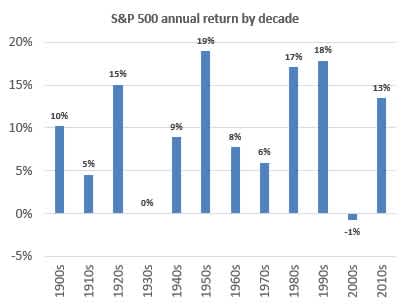

The first chart below shows the average annual US share market return in each decade since 1900. Over this 120-year period the average return in the US share market was 10% per annum. The chart shows that:

Annual returns vary significantly by decade

Annual returns for each decade are almost always positive

Only in the worst two decades did investors earn a return of less than 5% per annum (following the Great Depression and from the dotcom bubble to the GFC)

A decade of high returns is usually followed by a decade of lower returns (and vice versa)

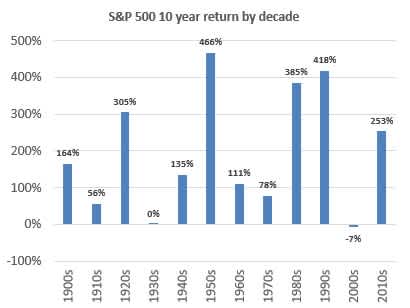

The second chart simply shows the cumulative returns for each decade. There were two decades where you didn’t make any money, but in the other 10 decades you made a return of between 56% and 466%. This shows the long-term gains that accrue to patient investors.

The share market can be a great way to build wealth over the long term. The key for investors is to make sure they have the appropriate timeframe and mindset. Investors need to ignore short-term noise and panicked headlines. Investors also need to make sure they have realistic expectations (which likely means lower returns over the next decade), but there is no reason for a long-term investor to be overly paranoid.